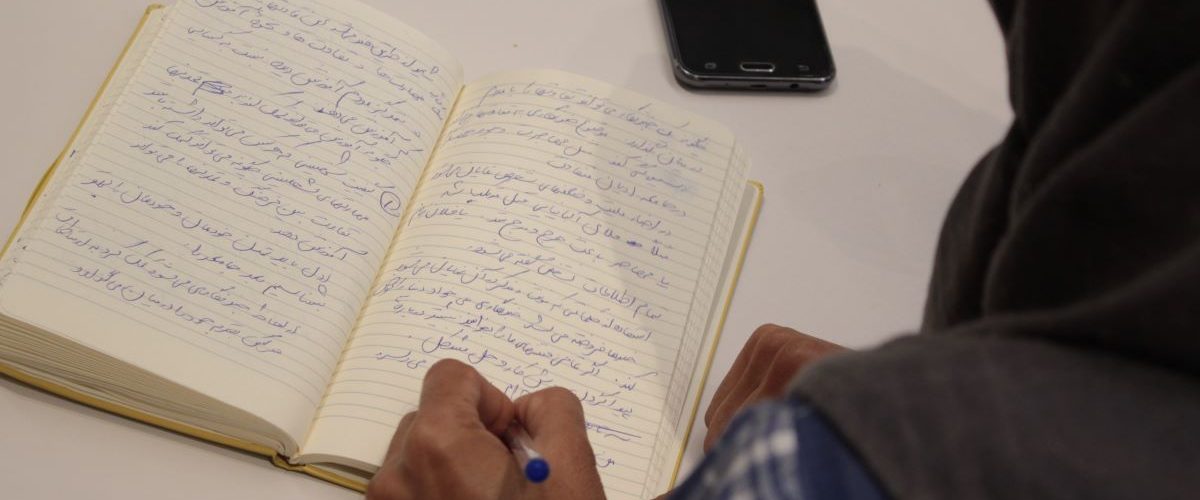

In life, people go through many stages and situations, school being the most important journey. School is the doorway to knowledge, it is where we learn how to identify good from bad, where we take the flight to wisdom. Our ethics are being formed under the guidance of knowledge and our days become filled with positive habits.

We must support the children and teenagers who are deprived of their right to education. That’s what the Ministry of Education in Greece has been doing since 2015, when people from the Middle East started coming to Europe seeking a better future. It has been helping so many migrants and refugees to continue their education and follow their dreams. That’s why we decided to talk with kindergarten and high school teachers in Malakasa, a town in eastern Attica, where one of the many refugee camps of the country is located.

“Εducation is the most important way for somebody who is not native to get introduced to, and involved with the local community, because, regardless of the the fact that you are not from Greece, you live in Greece,” says Mr. Kostas Kalemis, the educational coordinator for refugees at the camp of Malakasa, who has been working there for two years now.

At the moment an official kindergarten for refugee children from four to six years old is being run in three different containers inside the camp, while Solidarity Now and IOM have developed non-formal education programs to aid youth and adults.

As far as elementary and secondary education are concerned, refugee children and teenagers staying in the camp have been admitted to schools in Avlonas, Kapandriti, and the EPAL of Oropos. According to Mr. Kalemis, currently there are 452 refugee students, from Kindergarten to EPAL, attending schools in the greater area of Malakasa.

All courses are taught in Greek and, trust me, learning a foreign language in a foreign country is anything but easy. The major problem here is the lack of regular interpreters in schools. In the kindergarten of Malakasa, for example, the teachers do not follow the typical Greek program because they can’t really communicate with the pupils and their parents.

Mrs. Anna Faratzi, a kindergarten teacher at the camp of Malakasa says that “there are very few interpreters, and they are usually needed in more urgent situations and for bureaucratic issues. They don’t have any time to actually help here with the children. We are doing our best, meaning that we teach them some basic Greek words so that we can communicate. We can’t elaborate more on specific topics.”

The language barrier stands in the way of high school refugee students too. Mrs. Loukia Stefou, philologist at the 1st high school of Avlonas, follows a different method to overcome that obstacle: “Whenever I have to deal with the problem, I always make sure that there is at least one child in the class who can translate some very specific parts of the course in their mother tongue. I speak English, so I could do that, but I don’t like English to be spoken too much. I want them to familiarize themselves with the sound of Greek because it’s important for them. This is the second or third year in our school for some refugee children who speak Greek and fortunately they have Farsi as their common language.”

Two years ago there was a special afternoon class at the 1st high school of Avlonas which “normally” took place between 2pm and 6pm. It was a Reception Facility for Refugee Education (RFRE – DYEP in Greek). Mrs. Nantia Tsene, philologist and the director of the school, says “normally, if there’s sufficient teaching staff. Otherwise it operates from 2pm to 4pm, depending on the available staff.”

For Mrs. Faratzi the issue is that “they don’t live here permanently. People come and go. More people might come. There are children that started coming for two weeks and then had to go. In addition, there are children that live in the camp but do not attend systematically. They might come for a day and miss three days. They do not see this as their normal school. There are only a few parents who send their children every day. This makes it even more difficult for them to learn specific things. Many parents see this as a place for their children to spend some of their time, since they have many children at home.”

While many refugee children want to stay in Greece, their parents are just waiting for their papers so that they can travel to Europe. Mrs. Tsene confirms that: “Their attendance at school is not very systematic. Many of them quit, they move to other areas, we don’t know how they continue, many leave the country to other destinations. In other words, the children who have been here for three years are very few.”

For Mrs. Stefou that’s normal because “parents have a vision but our goals, purposes and aspirations are different. Children have found an environment in which they live their lives within their own context. We understand both sides. In any case, what I personally see is a need on the part of the children to follow a norm, even if that norm has a deadline, even if that norm will expire at some time, and this is what they seek. They feel that their feet stand on solid ground, not the ground of their homelands but the ground of Greece.”

Two or three years might not be enough time to assess the level of refugee integration into Greek society. However, if school is a miniature society, then we can already talk about refugee socialization.

Mrs. Stefou says you can also witness that during the break: “They hang out all together in the yard and play volleyball for example, they don’t play alone. This is a first step towards socialization. I believe that they are being driven by nature, because they are now in an age when they fall in love, and I think that this could happen and be the beginning for an osmosis between the children. I hope that they will stay here, that they will be grafted, as we will, and the trees that we will make together will be very beautiful with nice fruit.”

That’s correct, education gives us a knowledge of the world around us and changes it into something better. It helps us develop a perspective on life. It helps us build opinions and have points of view on things in life. Education is the most important medium for everyone, so try hard and reach your goals.

*This article has been published in issue #11 of “Migratory Birds” newspaper, which was released as an annex with “Efimerida ton Syntakton” newspaper (Newspaper of the Editors) on December 29th 2018.

Add comment