*As a new member of the “Migratory Birds” team, I decided that my first article should be about conditions in the camp in which I have been living for the past five months.

The refugee camp at Malakasa is one of many in the region of Attica. It is a 40-minute train ride away from Athens and was set up in 2016 as a result of the huge wave of migration into Greece that year. At the beginning of this summer, the number of residents increased further, due to refugees arriving from various hot spots on the Aegean islands. As there were not sufficient containers to house them, these people were obliged to live in tents. This led to a worsening of the living conditions in the camp. In the summer, they were obliged to leave their tents as soon as the sun rose and to sit in the shade of the trees in order to cope with the heat. They were given lukewarm water, which became hot within an hour. This state of affairs was not picked up by the media till August 27th, when torrential rain led to the flooding of the camp with rain and mud, making things even worse for those living in tents. The heat wave and the rain caused people to lose their patience and that is why dozens of them marched in protest on the National Road, leading to its closure. They also blocked the entrance to the camp, which meant that those who worked there couldn’t enter, and caused damage to the offices of the various organisations.

This article is based on both what I witnessed in the last five months at the Malakasa camp and on the information I obtained from interviews I carried out with residents and some of the managers of the organisations that agreed to talk to me.

On October 3rd 2018, I spoke with Mr Kostas Kalemis, Education Coordinator for Refugees at the Camp of Malakasa.

{The Malakasa Camp} was established as a refugee accommodation centre in 2016 following the surge in migrant arrivals that summer. People were accommodated in tents to begin with, but when the number of residents increased substantially, containers were brought in. Today, less than three years later, there are 192 containers, two oversize containers (essentially two big white buildings), one in front and one behind the mountain, and about 40 tents. I say “about” because their numbers decrease every day. The aim is to do away with them completely and replace them with containers so that people are accommodated with similar standards. Those in containers have air-conditioning, private bathroom facilities and a kitchen for cooking. Those in tents have to use a communal bath and shower, they have no electricity and eat food brought in by the army. This creates an inequality of services provided. Food is the same for everyone, because the scale of the population has increased since Easter compared to those registered in the camp, we register every week to receive food, although the number of people changes every ten days. For example, in schools, once every ten days, the situation of the students is determined. Due to the transfers, the students go from one school to another. By the end of May, we had six hundred and eighty people. According to official lists, 1,410 people live here. There are also 40 unaccompanied minors, who are of serious concern. Orphans and children have difficulty enrolling in school and education. They live in specific sections of the camp, the majority in containers, although there are two that live in a tent close to people they know. They range from 3-4 to 17 years old.

The next day (October 4th), the International Organization for Migration (IOM) gave a different answer to the same question.

“When the centre first started operating, it housed 500 people. Today there are 1,200 registered residents. The first increase in population happened in April 2016 with 1000 people then in June 2017 with 1,300. There are 20 tents and 200 containers. We expect that those remaining in tents will be moved to containers by the end of the month and the tents will be taken down”.

So, what is it like to live in a tent?

Alaa comes from Syria. He left his country as an amputee in one leg and crossed over to Mytilini from Turkey by boat. He then came to Malakasa where he has been living in a tent since April.

“Life in a tent is awful. It’s worse than being bombed and surrounded by destruction in Syria. The food is awful, totally unacceptable. The bread is stale. Conditions are bad. They cook the food, package it and bring it here. Sometimes it arrives raw. I am missing a leg yet they have placed me in a tent. What do you think my mental state is like?”

Fatima is the mother of three children from Afrin. She came to Greece five months ago. Three of those were spent on an island and the last two in a tent in Malakasa.

“They tell us that there are no containers. We left the island because we were classified as vulnerable, yet here we are. My two and a half year old daughter received burns from the cooking oil. I had to get the medicine and look after her myself. My children are young and won’t eat the food they bring us, even if I tell them off. There is no kitchen in the tent and no place to leave your children when you are cooking outside. I am pregnant and I fear for the baby I am carrying.”

The Ministry of Defence provides the food for those that don’t have a kitchen, i.e. all those living in tents.

When I asked Mr Kalemis what he thought about the food, he said:

“I have tried it, admittedly only once. I didn’t find anything wrong with it. Maybe the quantity is too small for a young person. I don’t really have an opinion, as it is not my responsibility. The truth is, this food is cooked for 4,000 people. Not just for this camp, but for all the camps in the region: Ritsona, Thiva, Inofita, Schimatari, everywhere. Our aim is to get everyone in a container by the end of October so they will have their own kitchen and will be able to cook their own food”.

Beyond the issues of accommodation and sustenance, camp residents are also concerned about the question of doctors. According to the IOM, the Hellenic Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (HCDCP) is responsible for medical welfare and treatment of camp residents.

I managed to speak with three nurses who work in the camp on weekdays under the community service programme of the Manpower Employment Organization (OAED) and more specifically at the Municipality of Oropos.

“Basically we are here to offer support to the HCDCP, which is the primary provider of health services and first aid to camp residents. We examine children and adults on a daily basis, always in the presence of a doctor, and we give vaccinations, also with a doctor present. In general terms, we provide assistance to the doctors who take all the decisions and are responsible for any incidents. There are two doctors and three nurses. If you are asking me whether this is sufficient, then the answer is no. According to the World Health Organization, there should be one doctor and one nurse for every 100 people.”

When I asked the nurse who helps in the paediatric centre, what are the most common health problems faced by patients, she replied:

“I see children with skin infections, viruses and a variety of infections, but most of all I deal with emergencies. Skin infections are mainly due to a lack of hygiene education, because the children haven’t learnt how to take care of themselves. Outbreaks of infections and viruses depend on the individual’s state of hygiene and their living conditions. I presume that soap and water are available to everyone, which means that it must be the exhaustion of the refugees as well as their circumstances that prevent them from adopting good habits of hygiene. Use soap and water, wash, make sure the children and all clothing are kept clean. There is a laundry here and the lady in charge of the storeroom hands out detergent so that people can wash their clothes. People have to look after themselves and their children; everyone is responsible for taking care of themselves. I am fairly sure that there is a water supply, because I am asked over and over again, and as far as I can see, all the basics are provided. So it must be a question of your own habits.”

According to Fatimah however “there is nothing. I gave my daughter a bath in the communal toilets and she came out in spots. Now I wash my children behind the tent, by boiling water and standing them up in a bucket.”

18-year-old Mohammed from Iraq spoke to us about the hygiene services. He has been in the Malakasa camp for about a year now. “There is a medical centre and there is a doctor”, he said, “but the medical centre is small and the team is not big enough. There is a Farsi interpreter but not an Arabic one. Half of us here speak Arabic. There is a month’s waiting list for a hospital appointment. By then the patient is dead”.

The nurses agree on the subject of interpreters.

“Our organisation doesn’t provide interpreters. We don’t provide doctors either, so we are not considered a medical team. We provide medical services under the supervision of the team that does provide the doctors. And they are the ones that can answer your questions regarding the provision of services. All I can say is that I work for 7 hours and 40 minutes every day, and during that time, I never get a break long enough for me to be able to say that I stopped and did nothing.

When I asked Fatimah how the doctors responded to her daughter’s case, she replied:

“They told me to take her to hospital, but how was I meant to go? This is not where I grew up, I don’t know where the hospital is, I don’t speak Greek. They don’t send ambulances. Unless you are dead.”

Alaa’s had this to say about the doctors:

“They don’t care, they don’t get involved with anything. If anyone goes to see them they just give them a couple of pills, Allah be with you, they don’t ask how you are, there is no care, you can’t even find an interpreter. You have to wait for one to be found. The way you have to wait if you need one of the camp’s employees.”

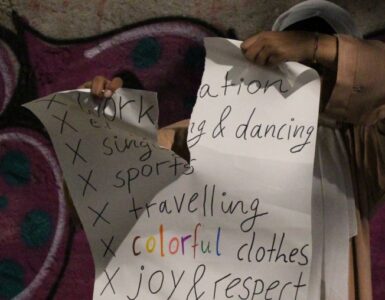

There are many people who regret coming to Greece. They say that had they known things would be like this, they would have stayed at home with the bombings going on overhead. We will not accept humiliation, injustice or exploitation. We do not deserve to be treated like this. Many things are not done correctly but they won’t stop unless people start getting punished. I hope that all of you who read these words will get a sense of what is going on and can understand how hard things are for us. I hope that in the end we can go back to our country safe and sound.

Photos by Narin Meho

Add comment